Spis treści

Opposing climate policy, defending coal industry employees and diversifying natural gas supplies – these are political declarations of Poland’s president-elect. Then there are also the declarations of Duda’a party PiS to consider: tilting at windmills, poor support for Poland’s nuclear power plant and for prosumer energy sector. The new president stands for the continuation along the lines of energy policy of PO-PSL government.

Opposing EU’s climate policy

Andrzej Duda, to be sworn in as Poland’s new president on August 6, made the opposition against the EU’s climate and energy policy as well as decarbonization one of the key elements of his election campaign.

Duda slammed the Polish government and incumbent president Bronislaw Komorowski for accepting a package the main objective of which is to cut greenhouse gases emission in the EU by 40% by 2030. The move threatens Poland’s coal-based energy security, Duda argued.

Duda slammed the Polish government and incumbent president Bronislaw Komorowski for accepting a package the main objective of which is to cut greenhouse gases emission in the EU by 40% by 2030. The move threatens Poland’s coal-based energy security, Duda argued.

{norelated}While it may not seem obvious, Duda’s position is a continuation of the rhetoric of the current government – who, incidentally, once scolded ex-president Lech Kaczynski for the approval of the current climate and energy package.

The PO-PSL coalition, similarly to PiS, opposed the package, vetoing attempts to tighten climate policy twice. Ultimately, the government yielded driven by pure pragmatism – another veto would pave the way for the European Commission to launch a legislative procedure under which Poland would have no more chances for blocking of the package. In exchange for its consent, Poland was granted significant reliefs for its energy enterprises.

Warsaw is an outsider in Europe in terms of its stance on climate and energy policy. Up to now, attempts to build a coalition of the states which should, in theory, strive to preserve the status quo of coal-based energy industry, have yielded negligible effects. The new president, even if he gets support of new diplomats from his own political circles after the autumn parliamentary election in Poland, stands no real chances for changing the European climate policy. Poland simply does not have any allies left in Europe for whom coal has an equal political importance.

In defense of miners

Also declarations made by both Duda and Komorowski as well as their respective political groupings on defending coal industry employees vary little. Particularly at the time when an election approaches. Interestingly, in the final round of the presidential election it was Bronislaw Komorowski who enjoyed a slightly higher support in the coal industry region Silesia, as shown by late exit poll of researcher Ipsos for broadcasters TVP, TVN24 and Polsat News (same as in the first round held two weeks earlier).

But as far as miners are concerned, the president’s powers are even more limited than in the case of climate policy. While Duda called on incumbent Komorowski to veto the bill on mining sector restructuring, he offered no alternative proposals for rescuing coal giant Kompania Weglowa which, by the time of signing the bill by the president, had run out of money for employee wages.

A potential PiS victory in the autumn parliamentary election will not give a chance for saving the closed mines, and certainly not for re-opening them (as PiS politicians declared). Any attempt on the part of the government to dodge the EU regulations on state aid for the mining industry (banned outright) would delay the company’s bankruptcy by a few weeks at most.

Still, it is yet to be seen if a potential new government, which may emerge if the autumn parliamentary election results in a reshuffle on the Polish political stage, will do any better in terms of solutions to the problem of mines. The assessment of the actions of the ownership supervision to date, provided by former deputy Prime Minister Elzbieta Bienkowska, as well as the state of affairs at Kompania Weglowa make it very clear that the benchmark has been set very low. But the words of Andrzej Duda on Poland having coal “for extraction for another 200 years” also indicate that the new head of state has no idea what he is talking about or else is using populist slogans. The same ones that have been fed to the miners for years, as an alternative to seeking a real solution for the post-mining Silesia region, at risk of repeating the scenario that has taken place in Walbrzych.

The new government will have a tough nut to crack – many more thousands of miners will lose their jobs in Silesia in the next 10 years as mines are in need of restructuring. Coal prices on global markets are well below the extraction costs of most of these mines. And no chances for higher prices are in sight. What is worse, Poland’s demand for coal is set to decline due to the new power blocks and improving energy efficiency of buildings.

Ambivalent nuclear power

Nuclear power is an issue on which both political groupings seem to have a similar view – and a very moderately optimistic one. On the bright side, Poland’s nuclear plant offers them a chance to imprint their names on the country’s history and provides opportunities for multi-billion contracts with trade and political partners – France and US – who have the relevant technologies.

But both are also aware of two problems – a financial (the cost of the first nuclear facility would hit some PLN 50 bln) and social (protests of activist citizen groups in Pomorze region) issue. During his election campaign, Andrzej Duda went so far as to flirt with the n-plant opponents, saying that the location of the facility in the area (i.e. in the coastal region) is absurd. Meanwhile, due to the factors such as technologies and costs that the president-elect apparently had no time to discuss, locating the plant anywhere else than in the immediate neighborhood of the Baltic Sea is impossible (a nuclear plant requires massive amounts of water for power production).

Tilting at windmills

Outgoing president Bronislaw Komorowski made a name for himself among renewable energy supporters by trying to impose limitations on inland wind farms. The proposal would give regional governments the powers to decide on the location of the farms in municipalities, while municipality heads would lose their authority to grant the wind farm permits independently. But the government removed the relevant fragments from the presidential bill of the act on landscape protection.

PiS caucus, led by MP Anna Zalewska, made an even further-reaching attempts to limit the options for wind farms locations. During the presidential campaign, Andrzej Duda tried to use these actions to court another group of voters by expressing his support for Zalewska in Zabkowice in Lower Silesia, declaring that he would push for passing a law that would prevent placing wind farms within a specified distance from homes.

Distributed generation

PiS MPs believe that an increase of the share of small, distributed generation energy sources such as photovoltaic panels, small wind power facilities or local biomass-fuelled heat and power plants should constitute an alternative to large wind farms. That fits in with the declarations made by Duda during last year’s campaign ahead of the election to the European Parliament when he said he was “rather for” the development of microinstallations. This information comes from the same candidate survey in which Duda gave a “very much for” answer to the question on stricter reductions of greenhouse gases emissions, for which Komorowski criticized him later during the pre-election campaign.

The ruling coalition politicians also declare their support for raising the share of distributed generation. Moreover, this direction is assumed in Poland’s current energy policy and the new system of renewables support. But it was PiS and junior coalition party PSL who finally forced the government and PO to increase the support for the segment.

Diversification without joint purchases

In the last year’s survey conducted among politicians by Latarnik Wyborczy, an online information tool on politicians’ views, Duda also supported a greater diversification of natural gas supplies. He was, however, against one of the flagship initiatives of the then-PM Donald Tusk, i.e. joint gas purchases.

Andrzej Duda further declared his support for the development of gas and electricity and power links with Poland’s neighbors. But such infrastructure, while a boost for energy security and a positive thing for consumers, harms the interests of the biggest state-run energy and gas companies. Poland’s new government will have to face these companies’ reluctance to open too broadly to imports of cheaper gas and electricity from the West.

Continuing on course

The two political groupings views seem to converge in nearly 90% as far as their declarations concerning energy issues are concerned. But the fundamental difference may consist in the way of the realization of the policy.

I know that changes in Poland will be painful in the short term, but it’s better to prepare the ground for them already. It’s important to learn from other countries’ experiences - says Philip Garner, Director General of Coal Pro, the confederation of UK coal producers in an interview on what went wrong in the UK's coal mining sector and what can happen in Poland.

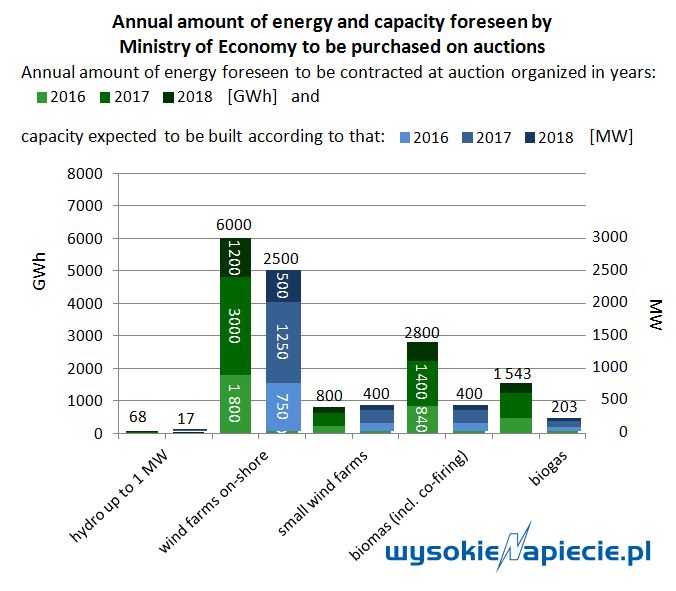

I know that changes in Poland will be painful in the short term, but it’s better to prepare the ground for them already. It’s important to learn from other countries’ experiences - says Philip Garner, Director General of Coal Pro, the confederation of UK coal producers in an interview on what went wrong in the UK's coal mining sector and what can happen in Poland. The Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Poland estimates that renewable energy auctions will take place only in the period between year 2016 and 2018. Investors can expect energy sales at 320-470 PLN per MWh. But the auctions may not be organized for everyone - according to information obtained by the Energy Legislation Observer of the WysokieNapiecie.pl website.

The Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Poland estimates that renewable energy auctions will take place only in the period between year 2016 and 2018. Investors can expect energy sales at 320-470 PLN per MWh. But the auctions may not be organized for everyone - according to information obtained by the Energy Legislation Observer of the WysokieNapiecie.pl website.