I know that changes in Poland will be painful in the short term, but it’s better to prepare the ground for them already. It’s important to learn from other countries’ experiences – says Philip Garner, Director General of Coal Pro, the confederation of UK coal producers in an interview on what went wrong in the UK’s coal mining sector and what can happen in Poland.

Justyna Piszczatowska: What is the situation on the coal market in the United Kingdom? Or maybe I should ask whether coal mining in the UK still exists?

Philip Garner: Last year domestic production was just less than 12 mln tonnes and we expect to reduce by a further 2 mln t this year. At privatisation this figure was 50 mln tonnes. We have declined very quickly since 1995. Knowing now what we know, things could have gone in a completely different direction.

JP: The Polish government is negotiating the terms of the support scheme for Kompania Weglowa with Brussels. The talks seem to have stalled in some areas, which probably means serious problems in the next months. If the biggest company goes bankrupt do you think the whole sector is doomed for extinction like in the UK?

PG: I know that changes in Poland will be painful in the short term, but it’s better to prepare the ground for them already. It’s important to learn from other countries’ experiences.

But Poland is in an entirely different situation. We produce more or less 90% of electricity from coal, while the UK has huge natural gas reserves and a far more diversified energy mix. So Poland has no alternative, while the UK simply made a choice.

PG: Yes. We do have a much more diverse energy mix, with just a modest share of coal, but we still do not supply the whole market in the UK from our own sources. Why? Because we have made the wrong moves in terms of the way we privatized the industry and the actions afterwards. This experience could be an important lesson for Poland.

What went wrong?

To start with – if you prepare an industry as a whole, or even just a company, for sale, you should look at the potential of the mine, not at its history. What the buyer has to take into consideration is coal reserves, local supply markets, future investment requirements operational risks, from geological and machinery and human point of view etc., and what are the perspectives.

This is a better way of looking at a whole company or even at an individual mine. Because people are more likely to look at it and say – “well it’s not doing well therefore we should close it” rather than “what are the best mines we have got available for the future and how do we make them more are attractive for sale”.

This kind of approach is present in the Polish government’s attitude because they separate the best mines from the worst ones in order to close the worst ones.

Are they judging on their past performance or future potential?

It’s a mixture of past performance and their perspectives, especially coal deposits. So I admit there is some rational attitude. But there is also a plan of making capital ties between the coal mines and energy companies.

In my opinion the idea that the preferred buyers for the coal mines would be the power plants is exactly right. In the UK we made a mistake, and I suppose you have at least partly done the same in Poland, by privatizing the power generating assets before we did the coal mines. So they became privately owned companies before the mining industry became endangered.

If those two privatizations had been done together and coal mines were in partnership or part of the same company as the power plants, we believe that that would have been much better relationship in terms of the way that the coal was mined and bought by the power plants. What we have created in the UK is that everything is determined by the international coal price. Any volatility in that price gives problems versus an underlying cost of production in the coal mine.

So if the price drops significantly and the selling price is lower than its cost of production, the company cannot operate unless it has significant cash reserves. But there are periods when the coal price are well in excess of the cost of production. At that point in time the power plants could gain back by having a “cost plus” arrangement instead of the market price. So to take a view at of how the coal is contracted and sold to the power plants is a much more pragmatic way of looking at coal mine-power plant relationship rather than supplier and customer relationship.

The thing is – Kompania Weglowa has negative cash reserves and it still does operate with costs of production below international coal prices.

The Polish government should resolve this problem as soon as possible. If not, what’s the alternative? You said yourself that in the short term Poland has no other choice but to use coal. So if it doesn’t use Polish coal, it would use imported one. And that imported coal would cost Poland far more than just the cost of fuel. Because it means that Polish miners are unemployed, therefore they don’t pay taxes, while the country has to buy fuel from other countries and pay in foreign currencies.

The gloomy scenario has already became reality in the UK. But I’m still quite skeptical about long-term cooperation between power plants and coal mines because the latter in Poland are in not effectively managed, not restructured and the biggest of them generates huge losses.

The emphasis has got to be on the question of what is the long term strategic value of having indigenous coal production . It lets you manage these price spikes. If you’ve got the same owners as the power plants, you can manage the strategic stocking of the coal as well and you can produce the right qualities. In most cases the power plants are designed to burn the coal that is produced nearby.

But now the global coal market is most likely to shift to low prices permanently.

When people ask can the Polish coal mine compete in the international market, the real question is what is the cost of not having them.

Don’t you think that merging coal mines with energy sector would mean lack of pressure on effectiveness in coal producing and ultimately higher energy prices for consumers? When everyone’s safe within the industry, there’s no reason for competing.

There would still be competition because the power plant owner would not necessarily be obliged to keep the coal mine operating if it’s cost of production consistently exceed the international coal price. In times such as now, when the coal prices are low, Polish coal mines cannot compete abroad. If I ask the same question in five years from now what would the answer be? Will prices fall further, remain as low or will they rebound? The real value of indigenous production is the ability to mitigate these market fluctuations.

You are talking about the ideal world in which energy companies would not be obliged to keep all the coal mines operating even though they are not profitable. Polish reality is that Kompania Weglowa is at the verge of bankruptcy and the government is doing everything to keep it alive, for example delays company’s payment of contributions to social security system. The fear of miners’ protests seems to be the strongest factor here. So I wouldn’t be surprised if after this hypothetical integration of energy and mining the government use a sense of pressure to keep them active no matter the financial circumstances.

At this point of time your workforce is objecting to the prospects of wholesale closures of the industry?

Exactly.

So the question is what is their alternative? In the UK a large closure program was announced and then it was partly changed and rescinded in 1992, then they embarked on the privatisation process. At the end of 1994, when it was privatised, the workforce were anticipating significant change in terms of employment and the ways of working. The biggest mistake that we made in the UK was not implementing significant change.

So the question I would ask you is how are Polish workers perceiving this threat to the coal mines? Is it something to totally resist or is there an acknowledgement that things need to change in order for the mines to continue?

Good question. There’s a lot of concern about the level of employment in the sector. Some people are probably wondering whether what we see now is an end of a certain era in the industry and there are lots of objections. Labour unions want to retain their status quo and they in a sense blackmail the government with a threat of fierce strikes. So if you ask me whether workers are aware of the fact that structural changes are inevitable and that the current situation can not last forever, the answer is no.

There are things that people have to recognize, like the fact that the long term future is better than keeping things as they are for the short term. The British government did quite a good job to do that at a certain point in time. But after the privatization the new owners chose not to change anybody’s way of working as they didn’t want to risk any disruptions from protesting workers. Once that happened, we lost the chance to change anything.

I know that changes in Poland will be painful in the short term, but it’s better to prepare the ground for them already. It’s important to learn from other countries’ experiences - says Philip Garner, Director General of Coal Pro, the confederation of UK coal producers in an interview on what went wrong in the UK's coal mining sector and what can happen in Poland.

I know that changes in Poland will be painful in the short term, but it’s better to prepare the ground for them already. It’s important to learn from other countries’ experiences - says Philip Garner, Director General of Coal Pro, the confederation of UK coal producers in an interview on what went wrong in the UK's coal mining sector and what can happen in Poland.

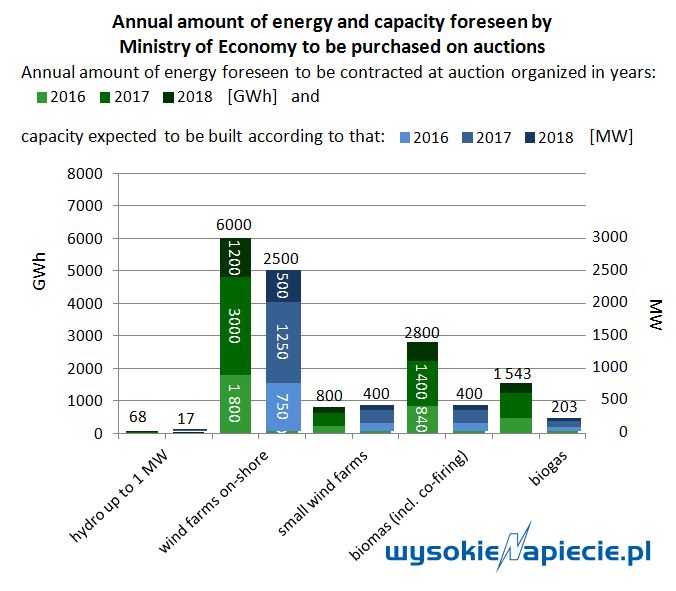

The Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Poland estimates that renewable energy auctions will take place only in the period between year 2016 and 2018. Investors can expect energy sales at 320-470 PLN per MWh. But the auctions may not be organized for everyone - according to information obtained by the Energy Legislation Observer of the WysokieNapiecie.pl website.

The Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Poland estimates that renewable energy auctions will take place only in the period between year 2016 and 2018. Investors can expect energy sales at 320-470 PLN per MWh. But the auctions may not be organized for everyone - according to information obtained by the Energy Legislation Observer of the WysokieNapiecie.pl website.